We Need More Seed Philanthropy

“Think small, get big. Think big, get small.” Herb Kelleher

In 2018, after 7 years and $600m spent, the Intensive Partnership for Effective Teaching declared failure. The non-profit effort designed to measure and manage teacher success was backed by the biggest minds and wallets (including Bill Gates) and mounds of research projecting its success. It was the latest in a string of efforts in education that had underwhelmed despite massive conviction—and resources.

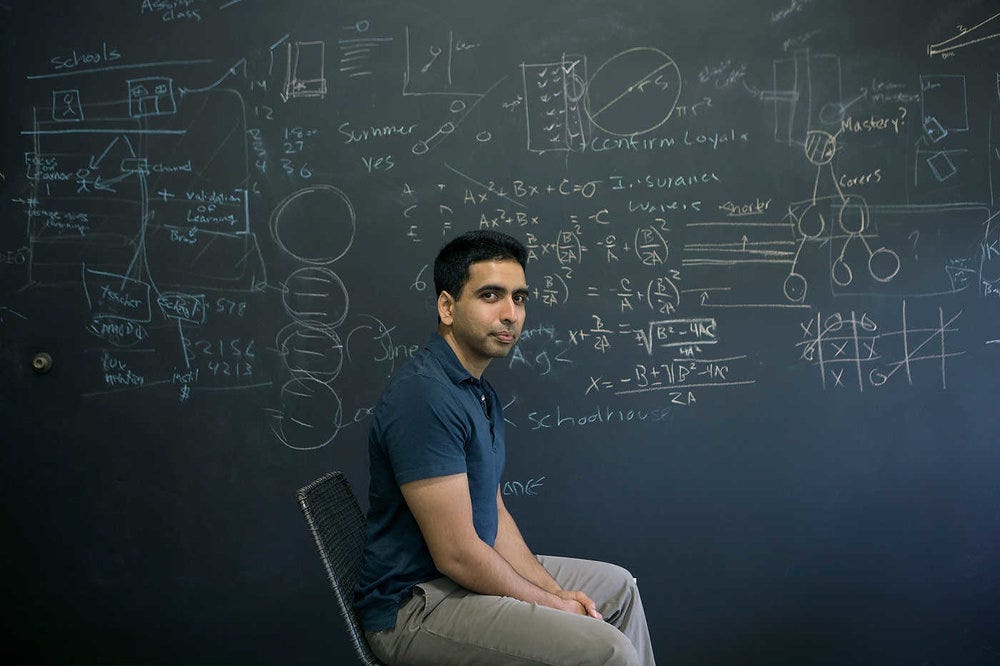

In 2009, the same year the Intensive Partnership started, a young hedge fund analyst named Salman Khan quit his job to publish and manage a site devoted to tutoring videos he had created to help his young cousin in school. He was backed by one small donor. In 2016, Khan Academy was serving over 12 million students per month in 30 languages. The Gates foundation is now a major backer.

Like many successes, the rise of Khan Academy was organic and unexpected. Its emergence came from a real-world problem, solved in a small way that just grew and grew as others saw value. It started small and scaled one user at a time—not based on a massive donation. No foundation was behind it —just a little seed money and a lot of time from a committed founder. This is how success happens in the for-profit world every day. The non-profit world surely needs more of it.

In the last decade, the movement of Effective Altruism has raised the bar for donors to scrutinize their gifts and prioritize those with the biggest measured impact. Inspired by the work of Peter Singer, the new class of mega donors (lead by the Gates Foundation) have set up large organizations to study projects to ensure maximum positive impact on the dollars going out the door. Problems are heavily researched and fundable solutions examined by subject matter experts (at least those with big resumés and experience in the chosen field). The question is would these organizations ever have backed Salman Khan in the early days? Well, they didn’t.

Effective altruism is at its best when it attacks clear misallocations—like major gifts to already mega-rich universities. Malcolm Gladwell famously ridiculed hedge fund manager John Paulson’s large gift saying: “If billionaires don’t step up, Harvard could be down to its last $30 billion.” There are arguments for these gifts (research and development, etc.) but it’s hard to debate ego-building isn’t a primary driver.

But Effective Altruism is a lot less helpful when it comes to giving for the purpose of solving complex issues—poverty, disease, racial achievement gaps, education, global warming. The movement proposes a cold hard rational view of impact and raises the bar on giving to solutions backed by evidence. But, these are complex, intractable problems for a reason—there are no easy answers. Money alone is absolutely not the issue. Yet, mega charities need solutions for their massive endowments. So when they see a bit of success—they pounce, pouring millions into scaling—just as happened with the Intensive Partnership. They have billions to spend after all. They want to play big and play fast to change the world. But failures often follow. The desire to get massive, fast impact is noble—but usually unsuccessful.

The problem with innovative ideas is they only look obvious in hindsight. Sam Altman of YC says, “Great ideas are fragile. They are easy to kill.” Big companies are terrible at innovation for just this reason. Big companies need big ideas. And big ideas need big budgets. And big budgets need great oversight. So safe, logical ideas in obvious opportunities get the funds and often get micromanaged to death. Consider the Zune iPod killer at Microsoft, rideshare at Ford, social networking at Google or countless other examples of massive enterprise innovation efforts.

Real innovation in business almost always arises from the highly inefficient venture community and the naive but optimistic founders they back. It takes hundreds of failures for any one big breakthrough. And the vast majority of the winners are unlikely in some obvious way. What makes us think non-profit work is any different?

How do we seed hundreds more Salman Khans? The Effective Altruism movement surely does not encourage more of them. Investment to pursue new and unorthodox ideas will result in too much failure. Luckily Khan had the time and resources to pursue his passion. Many don’t.

There are emerging models to help people with similar passions from the Genius Grants of the MacArthur foundation to Tyler Cowen’s new Emergent Ventures to YCombinator’s move to fund non-profits. We need more. The big foundations should create slices of capital for seed philanthropy. Pools should emerge so small donors can fund a portfolio of ideas.

Many will say this approach will miss big ideas and diminish the ambition so prevalent in foundations like Gates. Khan Academy, after all, is just a tutoring service that has not radically changed education. But big change takes time—and steps. Khan has cracked the code on the power of “one-to-many” teaching. It is a set of shoulders on which others will build. Its lessons will spawn many new ideas. My hunch is all revolutions need these sparks. Successes build over time, they are not born. All for-profit companies work this way. Who would give a startup $100 million on day 1? Seed investors are critical to businesses. When seeds blossom, Series A investors are there to keep them going, then growth capital and public markets. Gates, Bezos and many other large foundations play these big capital roles. But, the seed funds don’t really exist.

The great thing about seed philanthropy as a concept is it levels the playing field. It is daunting for anyone engaged in philanthropy to feel they can make a difference when Gates and Bezos are throwing billions around. As I look to establish my own giving strategies, I am excited to explore these concepts and how to move them forward. Updates to come.

Good Reads - Early March 2019

Noah Smith offers a much smarter alternative to the Green New Deal. Innovation focused with big dollars for R&D, trade incentives and carbon tax.

How good intentions went wrong on guaranteed student loans. Massive inflation and debt loads.

Worth revisiting in these times: Bertrand Russell’s 10 Commandments.

The libertarian, regenerative (and profitable) farmer Joel Salatin laments the WSJ report on failing mega farms.

Holistic and functional medicine goes big time - great interview with CEO of Cleveland Clinic on the changing view of health and getting to root causes (i.e. food, environment, lifestyle).